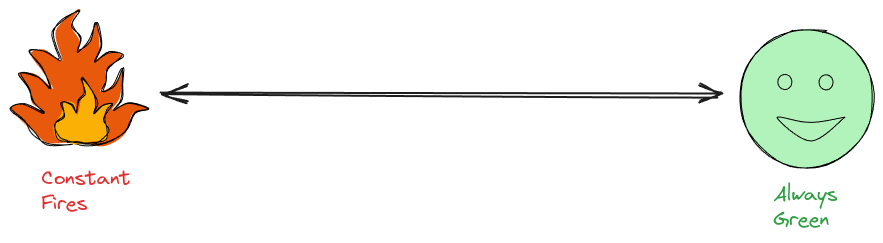

A common misconception is that on-call and livesite must be chaotic and hellish – folks erroneously assume that being on-call means fighting fires round the clock.

This school of thought regards people as “working” only if frequent high-severity off-hours calls wake them up. Managers are not left out too – they’re also expected to sacrifice their well-being at the altar of angry customers.

This way of thinking is wrong.

Similarly, some folks believe their services are perfect and always “green”. To this group, alerts are a minor distraction and should be ignored or avoided. A classic response is to restart the pesky machines, and everything is gonna be alright.

This way of thinking is also wrong.

Note: If every health metric is green every time, something somewhere is wrong.

The Spectrum

Your team probably falls somewhere between these two spectrums

I have worked on teams at both extremes and those in between. For six consecutive years working across various products, I had to be on call and had multiple late-night calls or multi-week outages. Those high-pressure situations are definitely not fun – you know something is off when folks start thinking of interviewing at other companies because they dread going on call.

These experiences taught me many techniques for achieving the sweet spot where customers are happy and engineers are shielded from chaos. I have since used these learnings to develop healthier teams with more sustainable operating schedules.

In this post, I’ll show you how to take your service maturity to the next level by identifying common failure patterns and suggesting proven techniques.

Common red flags

You may have experienced this in one form or another if you have been on call.

| Scenario | Symptom | Responsible Party |

|---|---|---|

| Pager hell | Never-ending outages and round-the-clock fires Burnt-out, apathetic engineers | The manager |

| Hero worship1 | Reliance on a few experts to mitigate issues2 A large surface area of services Services in maintenance mode | The leadership team |

| The alert cried wolf | Surface-level bandaid responses to alerts like ignoring the alerts, muting the alerts, and restarting servers | The manager |

| The Wild Wild West | Unclear expectations about livesite roles, incident severity levels, and toil responsibilities across the organization. Ad-hoc practices during outages Repeat outages because there are no incident review practices | The leadership team |

The two reasons

These scenarios might resonate with you, and you wonder what to do. Usually, most overlook the warning signs because they do not want to rock the boat. Eventually, chaos and blame ensue when a VP asks questions about a significant outage.

There are typically two reasons why red flags are ignored: a lack of will or a lack of skill. This article will concentrate on skills – specifically, enhancing your live-site practices.

Solving the will problem requires cultural change (Read The Cow and the Chicken: A Metaphor for Overcoming Resistance to Change).

Don’t miss the next post!

Subscribe to get regular posts on leadership methodologies for high-impact outcomes.

Common solutions that work

This section will go into some proven solutions.

Customer-focused monitoring

One of the most common mistakes people make is not connecting their monitoring efforts to the actual customer experience. It doesn’t matter if your service has a 100% uptime if your app is down – customers only care about the product working properly.

If you want to improve customer satisfaction, you need to take a customer-centric approach. It’s crucial to track all errors that customers encounter. This will help you to prioritize your efforts in addressing the issues that have the most significant impact. Remember, the success of your product depends on it functioning as expected.

The CAR framework offers a solution to the monitoring disconnect by establishing the interactions between the three entities: the customer, the application, and the underlying resources.

1-2-3 rule for Troubleshooting guides

Resolving any issue should take 1 developer 2 minutes at 3 am.

Ways to achieve this include doing drills or game days: you should not be training your engineers on real-life outages. I used to run drills for a past team, and the first drill was disastrous – we couldn’t even find a way to safely drain traffic from an internal cluster. By the 6th iteration, it was so smooth that we knew anyone on the team could do it within 3 minutes: the guides, alerts, and detection had been battle-tested enough.

Note: If it is tough to plan a game day or drill safely, that is enough of a signal that an outage will have a catastrophic impact on your organization.

Relentless pruning of decayed monitors via the STAT rule

Dead monitors breed apathy just as dead code breed bugs.

Are your teams plagued by a deluge of noisy alerts? More often than not, you have alert debt. It’s important to regularly review and remove outdated monitors, just like you would with dead code and dead features.

The STAT rule is here to the rescue (see the fantastic talk by Aditya Mukerjee at Monitorama 2018).

- S -> Supported: the alert has a clear owner and is not stale

- T -> Trusted: the signal-to-noise ratio is high; the alert does not cry wolf. It does not trigger false alarms

- A -> Actionable: There is a clear mitigation step to take when the alert fires. The troubleshooting guide is battle-tested and meets the 1-2-3 rule.

- T -> Triaged: The alert triggers are at the right severity level, matching business objectives.

Cull all monitors that do not comply with the STAT principle. Combing through all of them requires painstaking effort, but it’ll pay off in dividends.

Follow the sun (FTS)

Getting woken up at night is not fun. So, if you have a geographically dispersed organization (especially across timezones), take advantage of what you have by setting up an FTS schedule. This might require negotiations with your peers in other geos, but it usually works well if you can convince them.

The good thing is that the primitives (e.g., customer-focused monitoring, clear guides following the 1-2-3 rule, and STAT-ready monitors) should make this easier to achieve.

Repair items should be fixable within a month.

Assuming you have incident reviews, that should lead to repair items being created. A review meeting that doesn’t have any repair items is a joke.

- Long-term items: stay away from any repair item that will take more than 4 weeks to do, they rarely get done.

- Medium-terms: Doable within 2 to 4 weeks

- Short term: Must be completed within a week

A good tip is to have a deadline on these fixes and have them trump feature work. But what about all the fantastic features you want to build? There is a price for creating high-quality software at scale. This means you do not get 100% capacity to dedicate to the new and shiny; you have to maintain a healthy balance and tradeoff between keeping things going and working on adding new stuff.

You have to have org-wide buy-in and accountability on repair items. This requires org-wide buy-in and sponsorship if you don’t already have a practice for live site repair items. Especially since these must take top priority, supersede planned work, and be factored into project roadmaps.

This is what it means to be a mature product, and this is what is required.

Conclusion

A typical milestone on the service maturity journey is the need for standardized incident response and toil control practices. As services mature, regular on-call rotations emerge as necessary, and toil tasks become inevitable. These duties, which require non-zero work, become part and parcel of the job.

Despite their importance and occasional urgency (for outages), livesite and toil tasks are neither strategic nor differentiated. The opportunity cost of inefficiencies here is high – sprint targets can be easily derailed by fire-fighting. It is expensive to allocate significant chunks of team capacity to disruptive, interrupt-driven events.

I hope these suggestions help you turn the ship around.

Don’t miss the next post!

Subscribe to get regular posts on leadership methodologies for high-impact outcomes.

- Heroes signify organizational weaknesses. A communal reliance on heroes indicates fragility. ↩︎

- These folks have become so indispensable that their vacations are carefully planned. ↩︎

Discover more from CodeKraft

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Businesses gain a significant competitive advantage by investing in Custom Software Development Solutions. These solutions help cut unnecessary costs, focus on essential features, and offer long-term value by growing alongside your organization

LikeLike